It was early August and the morning horizon had started to turn from black to gray. My eyes strained to see where So Small my tiny 14-foot West Wight Potter, had strayed. "Oh my God! What have I gotten myself into?" The-seas rolling into my starboard quarter were 10 to 14 feet high, and occasional rogue waves were even higher.

I had tried to radio the Coast Guard at 2130 the evening before, to let them know where I was and that I was having a problem making a port. It wasn't a distress call, but I received no answer anyway. I still had hopes of making the Manitous as I continued sailing on through the pouring rain and crashing seas on automatic pilot.

As darkness set in, lightning threatened to blow my little craft out of the water. The wind veered to the east, causing the Potter to make more leeway. It was now impossible to reach the harbor on the eastern shore of South Manitou Island. I had just missed my last landfall.

The powerful wind slowly rotated counterclockwise. With a reefed headsail only, I could not make to weather and it was impossible to get a reefed mainsail up. My concern now was not to let So Small go aground on the southern shore of South Manitou or even worse, get washed into the shipwreck of the Francisco Morizon, a freighter that had run aground on a shoal south of the island.

The flashing light of the buoy marking the south side of the Manitou passage came into view off my starboard bow. A short time later, I sighted the buoy marking the north side. The range of these two lights would carry me safely past the western shore of the island as the storm drove me northwest. I sailed on through the blackness and waited for morning to unveil the madness of the sea.

At 0730, one hour after sunrise, So Small was taking a beating from the waves crashing into her quarter. Her tiny scupper couldn't drain the water cascading into her cockpit fast enough. Fearing that she would swamp I grabbed a bucket and started to bail.

With the gale showing no signs of abating, I decided to try the Coast Guard again. When I received no reply, I tried a general call on Channel 16.

"This is the vessel So Small. Can anybody out there hear me?"

Finally, I heard the golden words, "This is South Manitou Island. We read you loud and clear."

The South Manitou radio operator contacted the Coast Guard; they asked if I needed assistance. At this time a rogue wave hit So Small causing her to broach and take green water into her cockpit, filling it up over the seats. I ,swallowed my pride.

"I guess maybe I do."

With the winds averaging 30 knots and peaking over 50, the only landfall that I still might have made was the rocky shore of Door County, Wisconsin. Not a place one would want to land after dark in a gale!

The Frankfort Coast Guard dispatched a 44-foot rescue boat, but the craft had a tough time making speed in the rough water. Knowing that it was going to take a long time to reach me, the crew called for a rescue helicopter from Traverse City. Channel 22 was reserved for the emergency. I was in communication with South Manitou Island, and finally with the pilot of the Coast Guard helicopter. I gave him my location approximately 10 miles northwest of the Manitous. Later I found out I was actually 14 miles northwest of North Manitou, right in the center of Lake Michigan, with over 500 feet of water below my keel. For the next hour, I maintained a northwest course.

I looked out toward the Manitous as my boat crested a wave. There it was, the Coast Guard helicopter right in between the islands and my boat. I reached for the mike.

"This is the vessel, So Small, can you see me?"

"No," came the reply.

"Your helicopter is between me and the islands. You are very close."

"Now I see you," came the response. The helicopter changed course and in a few minutes was hovering overhead. It was a great relief to know that I was no longer alone. But my ordeal was far from over. I still had to keep So Small afloat, and the Coast Guard boat was still over 3 hours away. It became apparent now that I was suffering from exhaustion, seasickness, and dehydration. I was not aware that hypothermia was also setting in. This was as close to hell on earth as I ever wanted to be.

Lake Michigan Challenge

I conceived the idea of sailing, singlehanded, the full length of Lake Michigan three years before. Short weekend cruises were becoming a bore, and I needed a real challenge to prove the seaworthiness and plain fun of a pocket yacht. My Potter, purchased in 1978 and christened from the Seaman's Prayer, "Oh lord, the sea is so great and my boat is so small," seemed to be worthy of the task. A veteran of numerous voyages, she had been modified into a very well equipped mini-cruiser. A Force 8 gale on a previous cruise had convinced me to add double headsail furling so I could stay in the cockpit. Jiffy reefing was already on the main. I installed 8-foot oars to get through the breakers of unimproved outlets and to keep off the walls of improved channels if power was lost.

So Small also had a knot-log meter, wind speed meter, depthsounder, VHF radio, and automatic pilot. I was skeptical about the performance of an autopilot on a boat this small, but it did its job perfectly, except when heading straight into the seas.

Because Lake Michigan is cold and the weather can be unpredictable, I carry a full cold water survival work suit aboard, and my life vests have built-in safety harnesses. Preparing hot meals is a necessity while cruising in this area, so I installed a Sea Swing stove to the inside of the cabin's aft bulkhead, cooking my one-pot concoctions in a double boiler and cleaning the dishes with the hot water from the lower pot.

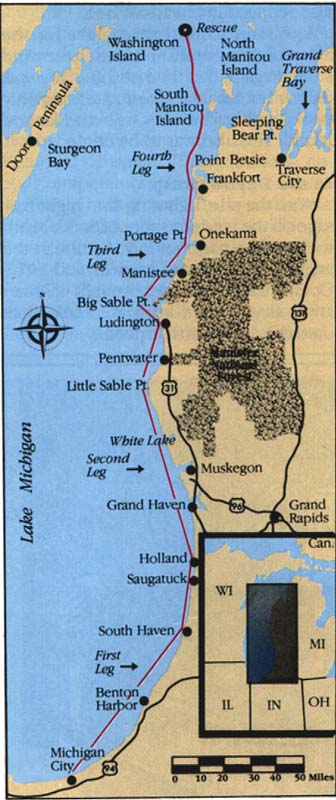

My summer free time is limited, so I divided the trip into several non-stop mini-cruises. The first leg covered approximately 100 miles from Michigan City, Indiana, to Holland, Michigan, with stopovers at South Haven and Saugatuck. Shipping lanes were not a problem, since I stayed a mile or two offshore and small boat traffic almost ceased by 2200. With my boat on autopilot, I sat back, drank coffee, and watched the lights along the shore.

Good sailing weather accompanied me on the next trek up the coast A starry sky welcomed me to the big lake as I departed from Holland just before dusk. This leg was an 80-mile sail to Ludington, a nonstop 20-hour jaunt. L passed the harbors of Grand Haven, Muskegon, White Lake, and Penrwater. The sail north of Little Point Sauble was a beautiful down-wind sleigh ride under twin headsails set wing and wing.

With 180 miles of the cruise now completed, I wanted more protection in the cockpit. I subsequently added a transom boarding ladder, a customized stem pulpit, and cockpit life lines, The foredeck aIready had the security of a factory-installed bow pulpit. I also added a bimini top for protection from exposure.

The third leg of the cruise was made in less desirable weather. I set sail from Ludington at sundown. The difficult beat around Big Point Sauble left me with the wind directly on my bow. The cloud cover was heavy, and there were no lights along the shoreline. I had to navigate by compass and depthsounder. At sunrise, the north wind stiffened and the sea began to build. Five hours passed In making the 8 miles from Manistee to the Portage Lake channel. I sailed through the channel onto Onekama where I called it quits.

Winds 15 to 20, Occasional Rain

It was August 9 before I could continue my cruise up Lake Michigan. My wife, Carol Ann, was planning to rendezvous in Leland on August 11. She would bring So Small and me back after I had sailed to the Manitous, around South Manitou from west to east and on to Leland.

I got away from Onekama at 1800 and started for the channel, sailing out into the face of another northern. Not wanting a repeat of the last leg, l brought her about and headed back into Portage Lake, where I anchored for the night.

I awoke to a slight drizzle and a light southeast wind. I prepared breakfast and turned on the VHF radio to get a weather report. "Southeast winds 15 to 20 knots later today with occasional rain." It didn't sound like the best of days, but it wasn't threatening either. I decided to make a go for it. I could always put into Frankfort if the weather got too bad. It would be drier in the cockpit with the bimini top left up, so I motor sailed out of the channel with the genoa only.

The rain fell steadily with torrential downpours occurring far too often. The sputtering of my little Seagull let me know that it did not appreciate getting wet. As the building seas became sloppy, the engine stopped altogether. I tilted and lashed the dead motor to the stem pulpit. As the wind became stronger, I partially furled the genoa and decided to abort the trip at Frankfort.

I had only a few hundred feet to reach the channel when another rain squall hit. As the wind velocity increased, it also shifted to the east by southeast making it impossible to sail into the harbor. Using my oars to row into this high wind was out of the question. I had to come about to keep from hitting the north wall.

Missing the Frankfort harbor was disappointing, but I wasn't overly concerned. After all, I still had three more possible landfalls; the next one to the lee of Point Betsie, where I thought I could work my way onto the beach. The wind had other ideas. It increased in velocity and took another shift counterclockwise to the east. The seas were now coming from two different directions. As we slid into the troughs of the larger waves, the wind would catch under the bimini top. Afraid that this could cause a knockdown, I unzipped the top, stowed it in the cabin, and lashed the bimini frame forward. I also reduced my headsail area.

I was on a heading straight for the Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes when the wind shifted again, this time pushing So Small further out into the lake and leaving only one possible landfall - South Manitou Island. This also was to be denied.

In the Devil's Grasp

With the rain, lightning, and night passage off the western shore of South Manitou Island a bad memory, I still had the angry building seas to deal with. The Coast Guard helicopter brought no guarantee that I could keep So Small afloat until the rescue boat arrived.

The wind was now coming from the northeast and showing no signs of diminishing. A freak wave off my port quarter was building higher than my masthead. As it peaked, it turned into a swirl of foam shooting skyward and making a sound like Fourth of July fireworks. I had been in bad weather, but I had never heard that sound from a wave before, nor do I care to again.

Another breaking wave slammed into So Small, filling her cockpit and broaching her again, this time causing her jib to back wind. The automatic pilot tried to get her back on course but jammed. I disconnected it and resheeted the jib for a reciprocal course. This new course reduced the ETA to the Coast Guard boat but added the risk of a knockdown. I observed a particularly large swell building off my port bow and tried to maneuver So Small upwind of the increasingly unstable crest, but it broke into a fury of white oscillating water, striking the little Potter on her port side. She succumbed and took a knockdown. The force catapulted me across the cockpit into the starboard lifeline so hard that I bent the rear stainless steel fitting. The lifeline held and kept me aboard as So Small righted herself. The cockpit was once again awash, and this time my bailing bucket was swept overboard. I retrieved a long stroke bilge pump from the cabin and pumped the cockpit.

The helicopter pilot informed me that he was running low on fuel and another helicopter was being dispatched from Traverse City. They dropped a smoke flare aft of my boat to help the relief pilot locate my position.

Sometime between 1100 and 1200, the rescue vessel appeared to port - the seas were so rough that I didn't see her approach until she was about 100 yards away. The coxswain asked me over the radio if I could make it forward to attach a line to the bow eye. With an affirmative, I locked the tiller and carefully made my way to the bow pulpit, where I wedged myself to keep from falling overboard. So Small slid into the trough of a large wave as the rescue boat heeled at 45 degrees near the crest, less than 50 feet away. A crewman threw a monkey fist across my deck. I grabbed the line but was unable to hang on to it. They circled for the second time with another miss. On the third try, I caught the line and made it fast to the bow eye.

Unfortunately, towing proved to be more difficult than any of us had anticipated. So Small's cockpit would swamp every time she yawed, and she would not tolerate any speed over 4 knots. Furthermore, as she rode over the larger swells, her bow would become airborne and crash into the troughs. I was afraid that the tow line might pull the bow eye out, or even worse, the whole boat would break up from the tremendous stress.

Visual communication was impossible in the rough seas. Although we were only 100 yards apart, I could see the Coast Guard boat less than 50 percent of the time.

My stomach was killing me. I hung over the side trying to relieve it, but there was nothing to relieve. I was growing weaker, and keeping my boat pumped out was becoming increasingly difficult. Water was gushing into the cabin through the centerboard well and had risen even with the tops of the bunks. The cockpit was flooded most of the time. I could hear the conversations of the helicopter and boat crew.

"We've got to get that guy out of there," and finally, "Skipper, do you want to come off your boat?"

Realizing now that if So Small was to be saved, it would have to be done by the Coast Guard, I said, "Okay."

"Okay, skipper, we will have to shorten the tow line and get another line to you to bring you aboard." They attempted to pass a light line, using the monkey fist again. The first try almost cost them the use of one of their engines as the line fell short, entangling their prop, but a Coast Guardsman quickly cut the line. They shortened the tow line some more and tried again, missing for the second time. The third try got the line close enough for me to grab. They then let out more tow line to get a safe distance.

It was scary having to jump into those chaotic seas, and I messed it up right from the beginning. The line only had a loop to hang on to. I should have looped it through itself and around my chest to be pulled with my back to the seas. Instead, I just hung on and jumped in. I was dragged on my stomach choking and gasping with water rushing into my mouth. It seemed like eternity! I was numb, cold, and exhausted. My left hand broke loose from the loop. "Is the rescue going to be a failure right here when we are so close?" I thought. I barely managed to hang on with my right hand until I was pulled to the side of the Coast Guard vessel. Three crewman could not pull me to the deck, and I was not of any help. I felt paralyzed. The coxswain left the wheel and I could hear someone say, "I don't care if you have to break his arms. Get that man aboard." With that the four guardsmen together hoisted me over the gunwale.

A rescue basket from the helicopter was lowered to the rear platform of the Coast Guard boat, but not without another incident. As they dropped the guide line for the basket, a metal fitting hit the chief mechanic on the head. He too would have to be removed by helicopter for medical attention. His bloody face was the last thing I saw as they lifted me off.

After getting me aboard, the helicopter flew to Frankfort where they transferred me by ambulance to the Paul Oliver Memorial Hospital. They checked my body temperature: it had dropped to 94 degrees. I was treated for hypothermia and admitted for overnight observation.

I will never be able to praise the crews of the Guard boat and helicopters enough. They were terrific in helping me and taking care of my boat. They also did their best to keep Carol Ann informed.

And though So Small and I were bruised )bruised and battered, except for the loss of some gear and electronics, we were not too worse for the wear.

That night, when Carol Ann entered my hospital room, she remarked, "Well, are ready to sail around the world?"

Not in a West Wight Potter," I replied.

After my near fatal ordeal, she was surprised that I would consider crossing any large body of water in any type of boat. But it will take a lot worse experience than this one to make me give up my love affair with the adventure of sailing and to forgo the remote places that I still want to see.

EPILOGUE

I do not want to belittle the West Wight Potter: She is a very seaworthy little craft, but she does have some faults. The Potter's internal freeboard is greatly reduced by a slot cut for the centerboard arm in the forward part of the trunk. Ralph Saylor has curved the arm on his Potter, allowing him to fill in the forward slot (see Cruising World, July 1982). So Small will have this same modification. This should greatly reduce the chance of water entering the cabin through the open centerboard trunk, but it would not completely eliminate it. Also, the internal freeboard would still be less than the external freeboard, which would be a problem if the boat were to swamp. In addition, the scupper in So Small's cockpit is too small for bad sea conditions. This can be easily corrected by adding another scupper.

So Small was advertised as having positive flotation. This might well be with a boat off the assembly line, but in trying to make her a better pocket cruiser, I have added to her weight. According to the Coast Guard crew who towed her in, she completely swamped and floated with only her bow out of the water when towing ceased. The next time So Small goes on a cruise, there will be air bags or more foam under her cockpit seats (see sidebar "Flotation Choices").

West Wight Potters have never been known to point well, and So Small is no exception. Saylor claims a taller rig on Wavewoloper helped her beat to weather. In the gale conditions I met, a taller rig would have been of no value, but a storm tri-sail just might have brought me into the safety of South Manitou Island.

There has always been controversy on where the VHF radio should be located on the priority list of equipment for a small boat (see "VHFs Explained," SBJ #53). Although my radio played a very important part in my rescue, I still cannot list it at the top. My craft's seaworthiness and its safety gear reserve that spot. My radio would have been of little use if I had not been able to keep So Small afloat and myself aboard until the Coast Guard arrived. However, I will never know if So Small would have gotten me alive to a landfall, and I'm very thankful that I had that radio aboard as my ace in the hole.

Preparation before one gets caught in a critical situation is the key to survival. The biggest error I made during my Lake Michigan ordeal was not having my survival suit on. I did not feel cold, and I was unaware that the silent killer, hypothermia, was setting in. Keeping dry with foul weather gear is futile in a small boat during those weather conditions. Even if So Small had stayed afloat, I might not have remained conscious until I reached land.